Session One: Introductions¶

Introductions¶

In which we meet each-other

Your instructors¶

Who are you?¶

Tell us a tiny bit about yourself:

- name

- programming background

- what do you hope to get from this class

Introduction to This Class¶

Python Programming

Course Materials Online¶

A rendered HTML copy of the slides for this course may be found online at:

http://codefellows.github.io/sea-f2-python-sept14/

Also there are homework descriptions and supplemental materials.

The source of these materials are in Chris’ gitHub repo:

http://github.com/PythonCHB/codefellows_f2_python

Class email list: We will be using this list to communicate for this class:

Canvas:

We will be using Canvas to track your homework submission, but not much else:

https://canvas.instructure.com/courses/881467

You should have received and email invitation to join the class.

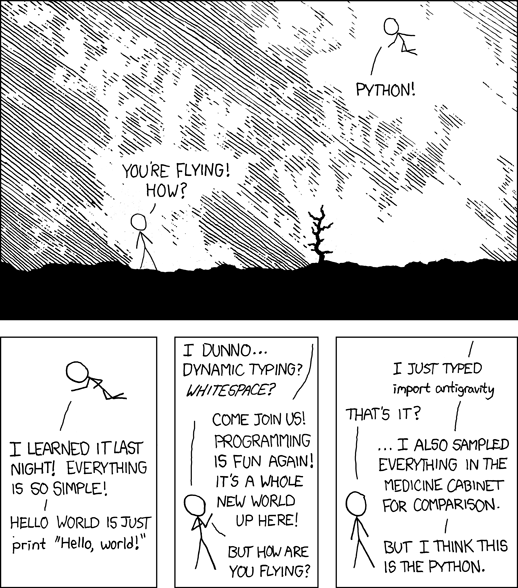

Python Features¶

Features:

- Unlike C, C++, C#, Java ... More like Ruby, Lisp, Perl, Javascript ...

- Dynamic – no type declarations

- Programs are shorter

- Programs are more flexible

- Less code means fewer bugs

- Interpreted – no separate compile, build steps - programming process is simpler

What’s a Dynamic language¶

Dynamic typing.

- Type checking and dispatch happen at run-time

In [1]: x = a + b

- What is a?

- What is b?

- What does it mean to add them?

- a and b can change at any time before this process

Strong typing.

In [1]: a = 5

In [2]: type(a)

Out[2]: int

In [3]: b = '5'

In [4]: type(b)

Out[4]: str

- everything has a type.

- the type of a thing determines what it can do.

Duck Typing¶

“If it looks like a duck, and quacks like a duck – it’s probably a duck”

If an object behaves as expected at run-time, it’s the right type.

Python Versions¶

Python 2.x

- “Classic” Python

- Evolved from original

Python 3.x (“py3k”)

- Updated version

- Removed the “warts”

- Allowed to break code

This class uses Python 2.7 not Python 3.x

- Adoption of Python 3 is growing fast

- A few key packages still not supported (https://python3wos.appspot.com/)

- Most code in the wild is still 2.x

- You can learn to write Python that is forward compatible from 2.x to 3.x

- We will be teaching from that perspective.

- If you find yourself needing to work with Python 2 and 3, there are ways to write compatible code: https://wiki.python.org/moin/PortingPythonToPy3k

Introduction to Your Environment¶

There are three basic elements to your environment when working with Python:

- Your Command Line

- Your Interpreter

- Your Editor

Your Command Line (cli)¶

Having some facility on the command line is important

We won’t cover this in class, so if you are not comfortable, please bone up at home.

I suggest running through the cli tutorial at “learn code the hard way”:

http://cli.learncodethehardway.org/book

There are a few things you can do to help make your command line a better place to work.

Part of your homework this week will be to do these things.

Your Interpreter¶

Python comes with a built-in interpreter.

You see it when you type python at the command line:

$ python

Python 2.7.5 (default, Aug 25 2013, 00:04:04)

[GCC 4.2.1 Compatible Apple LLVM 5.0 (clang-500.0.68)] on darwin

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>

That last thing you see, >>> is the “Python prompt”.

This is where you type code.

Try it out:

>>> print u"hello world!"

hello world!

>>> 4 + 5

9

>>> 2 ** 8 - 1

255

>>> print u"one string" + u" plus another"

one string plus another

>>>

When you are in an interpreter, there are a number of tools available to you.

There is a help system:

>>> help(str)

Help on class str in module __builtin__:

class str(basestring)

| str(object='') -> string

|

| Return a nice string representation of the object.

| If the argument is a string, the return value is the same object.

...

You can type q to exit the help viewer.

You can also use the dir builtin to find out about the attributes of a given object:

>>> bob = u"this is a string"

>>> dir(bob)

['__add__', '__class__', '__contains__', '__delattr__',

'__doc__', '__eq__', '__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__',

'__getitem__', '__getnewargs__', '__getslice__', '__gt__',

...

'rjust', 'rpartition', 'rsplit', 'rstrip', 'split', 'splitlines',

'startswith', 'strip', 'swapcase', 'title', 'translate', 'upper',

'zfill']

>>> help(bob.rpartition)

This allows you quite a bit of latitude in exploring what Python is.

In addition to the built-in interpreter, there are several more advanced interpreters available to you.

We’ll be using one in this course called iPython

Your Editor¶

Typing code in an interpreter is great for exploring.

But for anything “real”, you’ll want to save the work you are doing in a more permanent fashion.

This is where an Editor fits in.

Any good text editor will do.

MS Word is not a text editor.

Nor is TextEdit on a Mac.

Notepad is a text editor – but a crappy one.

You need a real “programmers text editor”

A text editor saves only what it shows you, with no special formatting characters hidden behind the scenes.

At a minimum, your editor should have:

- Syntax Colorization

- Automatic Indentation

In addition, great features to add include:

- Tab completion

- Code linting

- Jump-to-definition

- Interactive follow-along for debugging

Have an editor that does all this? Feel free to use it.

If not, I suggest Sublime Text:

Why No IDE?¶

I am often asked this question.

An IDE does not give you much that you can’t get with a good editor plus a good interpreter.

An IDE often weighs a great deal

Setting up IDEs to work with different projects can be challenging and time-consuming.

Particularly when you are first learning, you don’t want too much done for you.

YAGNI

Setting Up Your Environment¶

Shared setup means reduced complications.

Our Class Environment¶

We are going to work from a common environment in this class.

We will take the time here in class to get this going.

This helps to ensure that you will be able to work.

Step 1: Python 2.7¶

You have this already, RIGHT?

$ python

Python 2.7.5 (default, Aug 25 2013, 00:04:04)

[GCC 4.2.1 Compatible Apple LLVM 5.0 (clang-500.0.68)] on darwin

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> ^D

$

If not:

Step 2: Pip¶

Python comes with quite a bit (“batteries included”).

Sometimes you need a bit more.

Pip allows you to install Python packages to expand your system.

You install it by downloading and then executing an installer script:

$ curl -O https://bootstrap.pypa.io/get-pip.py

% Total % Received % Xferd Average Speed Time Time Time Current

Dload Upload Total Spent Left Speed

100 1309k 100 1309k 0 0 449k 0 0:00:02 0:00:02 --:--:-- 449k

$ python get-pip.py

(or go to: http://pip.readthedocs.org/en/latest/installing.html)

Once you’ve installed pip, you use it to install Python packages by name:

$ pip install foobar

...

To find packages (and their proper names), you can search the python package index (PyPI):

Step 3: Optional – Virtualenv¶

Python packages come in many versions.

Often you need one version for one project, and a different one for another.

Virtualenv allows you to create isolated environments.

You can then install potentially conflicting software safely.

For this class, this is no big deal, but as you start to work on “real” projects, it can be a key tool.

If you want to install it, here are some notes:

Step 4: Clone Class Repository¶

gitHub is an industry-standard system for collaboration on software projects – particularly open source ones.

We will use it this class to manage submitting and reviewing your work, etc.

Wait! Don’t have a gitHub account? Set one up now.

Next, you’ll make a copy of the class repository using git.

The canonical copy is in the CodeFellows organization on GitHub:

https://github.com/codefellows/sea-f2-python-sept14

Open that URL, and click on the Fork button at the top right corner.

This will make a copy of this repository in your github account.

From here, you’ll want to make a clone of your copy on your local machine.

At your command line, run the following commands:

$ cd your_working_directory_for_the_class

$ git clone https://github.com/<yourname>/sea-f2-python-sept14.git

(you can copy and paste that link from the gitHub page)

If you have an SSH key set up for gitHub, you’ll want to do this instead:

git@github.com:<yourname>/sea-f2-python-sept14.git

Remember, <yourname> should be replaced by your github account name.

Step 5: Install Requirements¶

As this is an intro class, we are going to use almost entirely features of standand library. But there are a couple things you may want:

iPython

$pip install ipython

If you are using SublimeText, you may want:

$ pip install PdbSublimeTextSupport

Introduction to iPython¶

iPython Overview¶

You have now installed iPython.

iPython is an advanced Python interpreter that offers enhancements.

You can read more about it in the official documentation.

Specifically, you’ll want to pay attention to the information about

The very basics of iPython¶

iPython can do a lot for you, but for starters, here are the key pieces you’ll want to know:

Start it up

$ipython

$ ipython

Python 2.7.6 (v2.7.6:3a1db0d2747e, Nov 10 2013, 00:42:54)

Type "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

IPython 2.0.0 -- An enhanced Interactive Python.

? -> Introduction and overview of IPython's features.

%quickref -> Quick reference.

help -> Python's own help system.

object? -> Details about 'object', use 'object??' for extra details.

This is the stuff I use every day:

- command line recall:

- hit the “up arrow” key

- if you have typed a bit, it will find the last command that starts the same way.

- basic shell commands:

- ls, cd, pwd

- any shell command:

- ! the_shell_command

- pasting from the clipboard:

- %paste (this keeps whitespace cleaner for you)

- getting help:

- something?

- tab completion:

- something.<tab>

- running a python file:

- run the_name_of_the_file.py

That’s it – you can get a lot done with those.

How to run a python file¶

A file with python code in it is a ‘module’ or ‘script’

(more on the distiction later on...)

It should be named with the .py extension: some_name.py

To run it, you have a couple options:

- call python on the command line, and pass in your module name

$ python the_name_of_the_script.py

- run iPython, and run it from within iPython with the run command

In [1]: run the_file.py

Basic Python Syntax¶

Code structure¶

Each line is a piece of code.

Comments:

In [3]: # everything after a '#' is a comment

Expressions:

In [4]: # evaluating an expression results in a value

In [5]: 3 + 4

Out[5]: 7

Statements:

In [6]: # statements do not return a value, may contain an expression

In [7]: print u"this"

this

In [8]: line_count = 42

In [9]:

It’s kind of obvious, but handy when playing with code:

In [1]: print u"something"

something

You can print multiple things:

In [2]: print u"the value is", 5

the value is 5

Python automatically adds a newline, which you can suppress with a comma:

In [12]: for i in range(5):

....: print u"the value is",

....: print i

....:

the value is 0

the value is 1

the value is 2

the value is 3

the value is 4

Any python object can be printed (though it might not be pretty...)

In [1]: class bar(object):

...: pass

...:

In [2]: print bar

<class '__main__.bar'>

Blocks of code are delimited by a colon and indentation:

def a_function():

a_new_code_block

end_of_the_block

for i in range(100):

print i**2

try:

do_something_bad()

except:

fix_the_problem()

Python uses whitespace to delineate structure.

This means that in Python, whitespace is significant.

(but ONLY for newlines and indentation)

The standard is to indent with 4 spaces.

SPACES ARE NOT TABS

TABS ARE NOT SPACES

These two blocks look the same:

for i in range(100):

print i**2

for i in range(100):

print i**2

But they are not:

for i in range(100):

\s\s\s\sprint i**2

for i in range(100):

\tprint i**2

ALWAYS INDENT WITH 4 SPACES

NEVER INDENT WITH TABS

make sure your editor is set to use spaces only –

ideally even when you hit the <tab> key

Values¶

- Values are pieces of unnamed data: 42, u'Hello, world',

- In Python, all values are objects

- Try dir(42) - lots going on behind the curtain!

- Every value belongs to a type

- Try type(42) - the type of a value determines what it can do

Literals for the Basic Value types:¶

- Numbers:

- floating point: 3.4

- integers: 456

- Text:

- u"a bit of text"

- u'a bit of text'

- (either single or double quotes work – why?)

- Boolean values:

- True

- False

(There are intricacies to all of these that we’ll get into later)

Values in Action¶

An expression is made up of values and operators

- An expression is evaluated to produce a new value: 2 + 2

- The Python interpreter can be used as a calculator to evaluate expressions

- Integer vs. float arithmetic

- (Python 3 smooths this out)

- Always use / when you want float results, // when you want floored (integer) results

- Type conversions

- This is the source of many errors, especially in handling text

- Python 3 will not implicitly convert bytes to unicode

- Type errors - checked at run time only

Symbols¶

Symbols are how we give names to values (objects).

- Symbols must begin with an underscore or letter

- Symbols can contain any number of underscores, letters and numbers

- this_is_a_symbol

- this_is_2

- _AsIsThis

- 1butThisIsNot

- nor-is-this

- Symbols don’t have a type; values do

- This is why python is ‘Dynamic’

Symbols and Type¶

Evaluating the type of a symbol will return the type of the value to which it is bound.

In [19]: type(42)

Out[19]: int

In [20]: type(3.14)

Out[20]: float

In [21]: a = 42

In [22]: b = 3.14

In [23]: type(a)

Out[23]: int

In [25]: a = b

In [26]: type(a)

Out[26]: float

Assignment¶

A symbol is bound to a value with the assignment operator: =

- This attaches a name to a value

- A value can have many names (or none!)

- Assignment is a statement, it returns no value

Evaluating the name will return the value to which it is bound

In [26]: name = u"value"

In [27]: name

Out[27]: u'value'

In [28]: an_integer = 42

In [29]: an_integer

Out[29]: 42

In [30]: a_float = 3.14

In [31]: a_float

Out[31]: 3.14

In-Place Assignment¶

You can also do “in-place” assignment with +=.

In [32]: a = 1

In [33]: a

Out[33]: 1

In [34]: a = a + 1

In [35]: a

Out[35]: 2

In [36]: a += 1

In [37]: a

Out[37]: 3

also: -=, *=, /=, **=, \%=

(not quite – really in-place assignment for mutables....)

Multiple Assignment¶

You can assign multiple variables from multiple expressions in one statement

In [48]: x = 2

In [49]: y = 5

In [50]: i, j = 2 * x, 3 ** y

In [51]: i

Out[51]: 4

In [52]: j

Out[52]: 243

Python evaluates all the expressions on the right before doing any assignments

Nifty Python Trick¶

Using this feature, we can swap values between two symbols in one statement:

In [51]: i

Out[51]: 4

In [52]: j

Out[52]: 243

In [53]: i, j = j, i

In [54]: i

Out[54]: 243

In [55]: j

Out[55]: 4

Multiple assignment and symbol swapping can be very useful in certain contexts

Deleting¶

You can’t actually delete anything in python...

del only unbinds a name.

In [56]: a = 5

In [57]: b = a

In [58]: del a

In [59]: a

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-59-60b725f10c9c> in <module>()

----> 1 a

NameError: name 'a' is not defined

The object is still there...python will only delete it if there are no references to it.

In [15]: a = 5

In [16]: b = a

In [17]: del a

In [18]: a

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-18-60b725f10c9c> in <module>()

----> 1 a

NameError: name 'a' is not defined

In [19]: b

Out[19]: 5

Identity¶

Every value in Python is an object.

Every object is unique and has a unique identity, which you can inspect with the id builtin:

In [68]: id(i)

Out[68]: 140553647890984

In [69]: id(j)

Out[69]: 140553647884864

In [70]: new_i = i

In [71]: id(new_i)

Out[71]: 140553647890984

Testing Identity¶

You can find out if the values bound to two different symbols are the same object using the is operator:

In [72]: count = 23

In [73]: other_count = count

In [74]: count is other_count

Out[74]: True

In [75]: count = 42

In [76]: other_count is count

Out[76]: False

Equality¶

You can test for the equality of certain values with the == operator

In [77]: val1 = 20 + 30

In [78]: val2 = 5 * 10

In [79]: val1 == val2

Out[79]: True

In [80]: val3 = u'50'

In [81]: val1 == val3

Out[84]: False

Operator Precedence¶

Operator Precedence determines what evaluates first:

4 + 3 * 5 != (4 + 3) * 5

To force statements to be evaluated out of order, use parentheses.

Python Operator Precedence¶

- Parentheses and Literals:

(), [], {}

"", b'', u''

- Function Calls:

- f(args)

- Slicing and Subscription:

a[x:y]

b[0], c['key']

- Attribute Reference:

- obj.attribute

- Exponentiation:

- **

- Bitwise NOT, Unary Signing:

~x

+x, -x

- Multiplication, Division, Modulus:

- *, /, %

- Addition, Subtraction:

- +, -

- Bitwise operations:

<<, >>,

&, ^, |

- Comparisons:

- <, <=, >, >=, !=, ==

- Membership and Identity:

- in, not in, is, is not

- Boolean operations:

- or, and, not

- Anonymous Functions:

- lambda

String Literals¶

You define a string value by writing a literal:

In [1]: u'a string'

Out[1]: u'a string'

In [2]: u"also a string"

Out[2]: u'also a string'

In [3]: u"a string with an apostrophe: isn't it cool?"

Out[3]: u"a string with an apostrophe: isn't it cool?"

In [4]: u'a string with an embedded "quote"'

Out[4]: u'a string with an embedded "quote"'

(what’s the ‘u‘ about?)

In [5]: u"""a multi-line

...: string

...: all in one

...: """

Out[5]: u'a multi-line\nstring\nall in one\n'

In [6]: u"a string with an \n escaped character"

Out[6]: u'a string with an \n escaped character'

In [7]: r'a "raw" string, the \n comes through as a \n'

Out[7]: 'a "raw" string, the \\n comes through as a \\n'

Keywords¶

Python defines a number of keywords

These are language constructs.

You cannot use these words as symbols.

and del from not while

as elif global or with

assert else if pass yield

break except import print

class exec in raise

continue finally is return

def for lambda try

If you try to use any of the keywords as symbols, you will cause a SyntaxError:

In [13]: del = u"this will raise an error"

File "<ipython-input-13-c816927c2fb8>", line 1

del = u"this will raise an error"

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

In [14]: def a_function(else=u'something'):

....: print else

....:

File "<ipython-input-14-1dbbea504a9e>", line 1

def a_function(else=u'something'):

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

__builtins__¶

Python also has a number of pre-bound symbols, called builtins

Try this:

In [6]: dir(__builtins__)

Out[6]:

['ArithmeticError',

'AssertionError',

'AttributeError',

'BaseException',

'BufferError',

...

'unicode',

'vars',

'xrange',

'zip']

You are free to rebind these symbols:

In [15]: type(u'a new and exciting string')

Out[15]: unicode

In [16]: type = u'a slightly different string'

In [17]: type(u'type is no longer what it was')

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-17-907616e55e2a> in <module>()

----> 1 type(u'type is no longer what it was')

TypeError: 'unicode' object is not callable

In general, this is a BAD IDEA.

Exceptions¶

Notice that the first batch of __builtins__ are all Exceptions

Exceptions are how Python tells you that something has gone wrong.

There are several exceptions that you are likely to see a lot of:

- NameError: indicates that you have tried to use a symbol that is not bound to a value.

- TypeError: indicates that you have tried to use the wrong kind of object for an operation.

- SyntaxError: indicates that you have mis-typed something.

- AttributeError: indicates that you have tried to access an attribute or method that an object does not have (this often means you have a different type of object than you expect)

Functions¶

What is a function?

A function is a self-contained chunk of code

You use them when you need the same code to run multiple times, or in multiple parts of the program.

(DRY)

Or just to keep the code clean

Functions can take and return information

Minimal Function does nothing

def <name>():

<statement>

Pass Statement (Note the indentation!)

def minimal():

pass

Functions: def¶

def is a statement:

- it is executed

- it creates a local variable

function defs must be executed before the functions can be called:

In [23]: unbound()

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-23-3132459951e4> in <module>()

----> 1 unbound()

NameError: name 'unbound' is not defined

In [18]: def simple():

....: print u"I am a simple function"

....:

In [19]: simple()

I am a simple function

Calling Functions¶

You call a function using the function call operator (parens):

In [2]: type(simple)

Out[2]: function

In [3]: simple

Out[3]: <function __main__.simple>

In [4]: simple()

I am a simple function

Functions: Call Stack¶

functions call functions – this makes an execution stack – that’s all a trace back is

In [5]: def exceptional():

...: print u"I am exceptional!"

...: print 1/0

...:

In [6]: def passive():

...: pass

...:

In [7]: def doer():

...: passive()

...: exceptional()

...:

You’ve defined three functions, one of which will call the other two.

Functions: Tracebacks¶

In [8]: doer()

I am exceptional!

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ZeroDivisionError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-8-685a01a77340> in <module>()

----> 1 doer()

<ipython-input-7-aaadfbdd293e> in doer()

1 def doer():

2 passive()

----> 3 exceptional()

4

<ipython-input-5-d8100c70edef> in exceptional()

1 def exceptional():

2 print u"I am exceptional!"

----> 3 print 1/0

4

ZeroDivisionError: integer division or modulo by zero

Functions: return¶

Every function ends by returning a value

This is actually the simplest possible function:

def fun():

return None

if you don’t explicilty put return there, Python will:

In [9]: def fun():

...: pass

...:

In [10]: fun()

In [11]: result = fun()

In [12]: print result

None

note that the interpreter eats None

Only one return statement will ever be executed.

Ever.

Anything after a executed return statement will never get run.

This is useful when debugging!

In [14]: def no_error():

....: return u'done'

....: # no more will happen

....: print 1/0

....:

In [15]: no_error()

Out[15]: u'done'

However, functions can return multiple results:

In [16]: def fun():

....: return (1, 2, 3)

....:

In [17]: fun()

Out[17]: (1, 2, 3)

Remember multiple assignment?

In [18]: x,y,z = fun()

In [19]: x

Out[19]: 1

In [20]: y

Out[20]: 2

In [21]: z

Out[21]: 3

Functions: parameters¶

In a def statement, the values written inside the parens are parameters

In [22]: def fun(x, y, z):

....: q = x + y + z

....: print x, y, z, q

....:

x, y, z are local symbols – so is q

Functions: arguments¶

When you call a function, you pass values to the function parameters as arguments

In [23]: fun(3, 4, 5)

3 4 5 12

The values you pass in are bound to the symbols inside the function and used.

The if Statement¶

In order to do anything interesting at all (including this week’s homework), you need to be able to make a decision.

In [12]: def test(a):

....: if a == 5:

....: print u"that's the value I'm looking for!"

....: elif a == 7:

....: print u"that's an OK number"

....: else:

....: print u"that number won't do!"

In [13]: test(5)

that's the value I'm looking for!

In [14]: test(7)

that's an OK number

In [15]: test(14)

that number won't do!

There is more to it than that, but this will get you started.

Enough For Now¶

That’s it for our basic intro to Python

Before next session, you’ll use what you’ve learned here today to do some exercises in Python programming

Homework¶

Four Tasks by Next Monday

Task 1¶

Tell Us About Yourself

This is a way for you to learn a bit about gitHub, and how you are going to submit most of your homework.

- Create a new folder in the students folder in the class repository.

- Create the folder in your clone of your fork of the repository.

- Name it with your own name in CamelCase, like: ChrisBarker.

- In the folder create one new file, named README.md

- In that new file, write up a few paragraphs about yourself.

- Use proper markdown syntax. (or reStructuredText)

- Include at least two headings, of different levels.

- Include at least one link.

- Using git add, add the new folder and file to your clone of the repository.

- Using git commit, commit your changes to your clone (write a good commit message). If you later edit your file, don’t forget to commit those changes too.

- Using git push, push your commits to your fork on GitHub.

- In GitHub’s Web UI, make a pull request to the original CodeFellows repository.

Task 2¶

Set Up a Great Dev Environment

Make sure you have the basics of command line usage down:

Work through the supplemental tutorials on setting up your Command Line for good development support.

Make sure you’ve got your editor set up productively – at the very very least, make sure it does Python indentation well.

Advanced Editor Setup:

If you are using SublimeText, here are some notes to make it super-nifty:

Setting up SublimeText .

At the end, your editor should support tab completion and pep8 and pyflakes linting. Your command line should be able to show you what virtualenv is active and give you information about your git repository when you are inside one.

If you are not using SublimeText, look for plugins that accomplish the same goals for your own editor. If none are available, please consider a change of editor.

Task 3¶

Python Pushups

To get a bit of exercise solving some puzzles with Python, work on the Python exercises at CodingBat.

Begin by making an account on the site. Once you have done so, go to the ‘prefs’ link at the top right and enter your name so we know who you are.

In addition, add the following email address to the ‘Share To’ box. This will allow your instructors to see the work you have done.

pyinstructor@codefellows.com

There are 8 sets of puzzles. Do as many as you can, starting with the Warmups.

Please Note: Do Not send emails to the above email address, they will not be answered.

Task 4¶

Explore Errors

Create a new directory in your personal folder in the students folder of the class repository:

$ mkdir session01 $ cd session01

Make sure you create it in your clone of your fork of the repository.

Add a new file to it called break_me.py

Use git add to add the file to the repository.

- In the break_me.py file write four simple Python functions:

- Each function, when called, should cause an exception to happen

- Each function should result in one of the four common exceptions from our

lecture.

- for review: NameError, TypeError, SyntaxError, AttributeError

(hint – the interpreter will quit when it hits a Exception – so you can comment out all but the one you are testing at the moment)

- Use the Python standard library reference on Built In Exceptions as a reference

- Use git commit to commit changes you make to your clone

- Make frequent, small commits using git commit when working.

- Write clear, concise commit messages that explain what you are doing.

- When you are finished with your work, use git push to push your changes to your fork on GitHub.

- Finally, issue a pull request to the original CodeFellows repository with your work.