Getting Data In¶

We’ve talked over the last few sessions about ways of consuming data from online web services.

In most cases, when you use a web service, you send some data to that service so that it can use that information as parameters for whatever process it performs.

How does the data we send to a web service end up getting used by that service?

Environments¶

A computer has an environment:

In *nix, you can see this in a shell:

$ printenv

TERM_PROGRAM=iTerm.app

...

Changing Your Environment¶

This can be manipulated. In a bash shell we can do this:

$ export VARIABLE='some value'

$ echo $VARIABLE

some value

Once you change them, these new values are now part of the environment for as long as your shell session remains alive.

In *nix:

$ printenv

TERM_PROGRAM=iTerm.app

...

VARIABLE=some value

Environment in Python¶

From within Python, the same environment can be seen:

$ python

...

>>> import os

>>> print os.environ['VARIABLE']

some_value

>>> print os.environ.keys()

['VERSIONER_PYTHON_PREFER_32_BIT', 'VARIABLE',

'LOGNAME', 'USER', 'PATH', ...]

And of course, from within Python you can alter os environment values:

>>> os.environ['VARIABLE'] = 'new_value'

>>> print os.environ['VARIABLE']

new_value

But changing that value inside Python doesn’t change the original value, outside Python:

>>> ^D

$ echo this is the value: $VARIABLE

this is the value: some_value

<OR>

C:\> \Users\Administrator\> echo %VARIABLE%

'some value'

So what does this all mean?

Process Environments¶

The Python interpreter, when you start it up, is a subprocess of the

terminal session from which you started it.

- Subprocesses inherit their environment from their Parent

- Parents do not see changes to environment in subprocesses

- In Python, you can actually set the environment for a subprocess explicitly

subprocess.Popen(args, bufsize=0, executable=None,

stdin=None, stdout=None, stderr=None,

preexec_fn=None, close_fds=False,

shell=False, cwd=None, env=None, # <-------

universal_newlines=False, startupinfo=None,

creationflags=0)

Environments Online¶

When it comes to building online scripts that can consume incoming data, it is this concept of an environment that serves to connect data from an incoming request to the process(es) that handle it.

We’ll take a quick look at two implementations of this idea, the CGI standard and the WSGI specification.

CGI¶

CGI is little more than a set of standard environmental variables

First discussed in 1993, formalized in 1997, the current version (1.1) has been in place since 2004.

The preamble to rfc3875 has the following text:

This memo provides information for the Internet community. It does not specify an Internet standard of any kind.

The CGI Meta-Variables¶

This means that although there is a general agreement about what should be in the CGI environment, there is no law that enforces this. You cannot count on any specific information actually being there.

Here’s a list of the commonly understood environmental Meta-Variables in CGI:

4. The CGI Request . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

4.1. Request Meta-Variables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

4.1.1. AUTH_TYPE. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

4.1.2. CONTENT_LENGTH . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

4.1.3. CONTENT_TYPE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

4.1.4. GATEWAY_INTERFACE. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

4.1.5. PATH_INFO. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

4.1.6. PATH_TRANSLATED. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

4.1.7. QUERY_STRING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

4.1.8. REMOTE_ADDR. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

4.1.9. REMOTE_HOST. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

4.1.10. REMOTE_IDENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

4.1.11. REMOTE_USER. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

4.1.12. REQUEST_METHOD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

4.1.13. SCRIPT_NAME. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

4.1.14. SERVER_NAME. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

4.1.15. SERVER_PORT. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

4.1.16. SERVER_PROTOCOL. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

4.1.17. SERVER_SOFTWARE. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

CGI In Python¶

You can run CGI scripts that you write on any web server that supports CGI:

- Apache

- IIS (on Windows)

- Some other HTTP server that implements CGI (lighttpd, ...?)

Note that nginx is not on this list. The designers of that server have

specifically stated that they will not support CGI.

The Python standard library also provides a simple CGI server in the

CGIHTTPServer module.

This module provides some benefits that will help if you need to debug CGI.

To see CGI in action, let’s create a very simple Python CGI script and run it, using the built-in server.

To begin with, create a folder called cgitests. Then create a folder

inside that called cgi and inside that, create a script called cgi.py:

heffalump:tests cewing$ mkdir -p cgitests/cgi-bin

heffalump:tests cewing$ touch cgitests/cgi-bin/cgi_1.py

heffalump:tests cewing$ git status

heffalump:tests cewing$ cd cgitests/

heffalump:cgitests cewing$ tree .

.

└── cgi-bin

└── cgi_1.py

Next, open cgi.py in your text editor and enter the following code:

#!/usr/bin/env python

import cgi

cgi.test()

Once you’ve saved that file, start the Python CGI server.

!!Make sure you are in the cgitests directory, not the cgi directory!!

heffalump:cgitests cewing$ python -m CGIHTTPServer

Serving HTTP on 0.0.0.0 port 8000 ...

Now, open your browser and point it at the following address:

http://localhost:8000/cgi-bin/cgi_1.py

What do you see? What’s in the terminal where the server is running?

127.0.0.1 - - [25/Feb/2014 10:31:14] "GET /cgi-bin/cgi_1.py HTTP/1.1" 200 -

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7/CGIHTTPServer.py", line 253, in run_cgi

os.execve(scriptfile, args, env)

OSError: [Errno 13] Permission denied

127.0.0.1 - - [25/Feb/2014 10:31:14] CGI script exit status 0x7f00

Notice that the response the server sent back to the client has the HTTP status

200. As far as your web browser is concerned, nothing went wrong. But

clearly something is wrong.

CGI is famously difficult to debug. There are reasons for this:

- CGI is designed to provide access to runnable processes to the internet

- The internet is a wretched hive of scum and villainy

- Revealing error conditions can expose data that could be exploited

There are a couple of important facts that are related to the way CGI processes are run:

- The script must include a shebang so that the system knows how to run it.

- The script must be executable.

- The executable named in the shebang will be called as the nobody user.

- This is a security feature to prevent CGI scripts from running as a user with any privileges.

- This means that both the script and the executable from the script shebang must be one that anyone can run.

Debugging CGI¶

We’ve got the shebang, but if you look, our script is not executable. Let’s fix that.

heffalump:cgitests cewing$ ls -l cgi-bin/

total 0

-rw-r--r-- 1 cewing staff 0 Feb 25 10:18 cgi_1.py

heffalump:cgitests cewing$ chmod 755 cgi-bin/cgi_1.py

heffalump:cgitests cewing$ ls -l cgi-bin/

total 0

-rwxr-xr-x 1 cewing staff 0 Feb 25 10:18 cgi_1.py

heffalump:cgitests cewing$

Once you have fixed that, terminate your CGI server and restart it:

heffalump:cgitests cewing$ python -m CGIHTTPServer

Serving HTTP on 0.0.0.0 port 8000 ...

What do you see now?

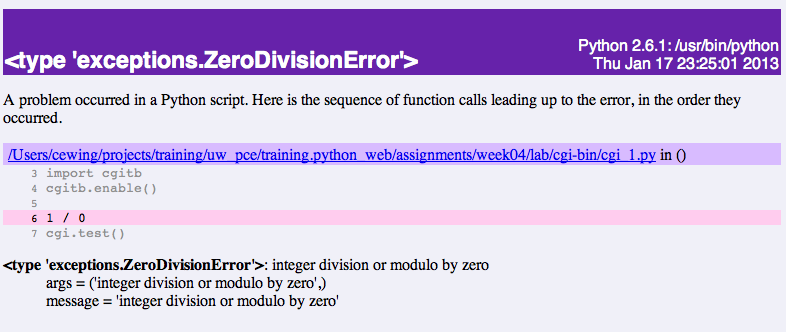

In CGI, problems with permissions can lead to failure. So can scripting errors.

Back in your editor, add the following line of code before the call to

cgi.test()

1 / 0

Reload your browser. What happens now? What does your browser tell you? How about the server terminal?

Back in your editor, add the following lines, just below import cgi:

import cgitb

cgitb.enable()

Now, reload again. You should see something like this.

Let’s fix the error from our traceback. Edit your cgi_1.py file to match:

#!/usr/bin/python

import cgi

import cgitb

cgitb.enable()

cgi.test()

Where It All Begins¶

We’ve said that CGI is largely a set of agreed-upon environmental variables.

We’ve seen how environmental variables are found in python in os.environ

We’ve also seen that at least some of the variables in CGI are not in the standard set of environment variables.

Where do they come from?

Let’s find ‘em. In a terminal (on your local machine, please) fire up python:

>>> import CGIHTTPServer

>>> CGIHTTPServer.__file__

'/big/giant/path/to/lib/python2.6/CGIHTTPServer.pyc'

Copy this path and open the file it points to (without the ‘c’) in your text editor

From CGIHTTPServer.py, in the CGIHTTPServer.run_cgi method:

# Reference: http://hoohoo.ncsa.uiuc.edu/cgi/env.html

# XXX Much of the following could be prepared ahead of time!

env = {}

env['SERVER_SOFTWARE'] = self.version_string()

env['SERVER_NAME'] = self.server.server_name

env['GATEWAY_INTERFACE'] = 'CGI/1.1'

env['SERVER_PROTOCOL'] = self.protocol_version

env['SERVER_PORT'] = str(self.server.server_port)

env['REQUEST_METHOD'] = self.command

...

ua = self.headers.getheader('user-agent')

if ua:

env['HTTP_USER_AGENT'] = ua

...

os.environ.update(env)

...

And that’s it, the big secret. The server takes care of setting up the environment so it has what is needed.

Delivering Responses¶

Now, in reverse. How does the information that a script creates end up in your browser?

A CGI Script must print its results to stdout.

Use the same method as above to import and open the source file for the

cgi module. Note what test does for an example of this.

What the Server Does:

- parses the request

- sets up the environment, including HTTP and SERVER variables

- figures out if the URI points to a CGI script and runs it

- builds an appropriate HTTP Response first line (‘HTTP/1.1 200 OK\r\n’)

- appends what comes from the script on stdout and sends that back

What the Script Does:

- names appropriate executable in it’s shebang line

- uses os.environ to read information from the HTTP request

- builds any and all appropriate HTTP Headers (Content-type:, Content-length:, ...)

- prints headers, empty line and script output (body) to stdout

User Input¶

All this is well and good, but where’s the dynamic stuff?

It’d be nice if a user could pass form data to our script for it to use.

In HTTP, these types of inputs show up in the URL query (the part after

the ?):

http://myhost.com/script.py?a=23&b=37

In the cgi module, we get access to this with the FieldStorage class:

import cgi

form = cgi.FieldStorage()

stringval = form.getvalue('a', None)

listval = form.getlist('b')

- The values in the

FieldStorageare always strings - Every key/value pair in the query will be in the

FieldStorage .getvalue()allows you to return a default, in case the field isn’t present.getlist()always returns a list: empty, one-valued, or as many values as are present

CGI Problems¶

CGI is quite useful, but there are problems:

- Code is executed in a new process

- Every call to a CGI script starts a new process on the server

- Starting a new process is expensive in terms of server resources

- Especially for interpreted languages like Python

How do we overcome these issues?

The most popular approach is to have a long-running process inside the server that handles CGI scripts.

FastCGI and SCGI are existing implementations of CGI in this

fashion. The Apache module mod_python offers a similar capability for

Python code.

- Each of these options has a specific API

- None are compatible with each-other

- Code written for one is not portable to another

This makes it much more difficult to share resources

WSGI¶

Enter WSGI, the Web Server Gateway Interface.

Where other alternatives are specific implementations of CGI, WSGI is itself a new specification, not an implementation.

WSGI is generalized to describe a set of interactions, so that developers can write WSGI-capable apps and deploy them on any WSGI server.

Read the WSGI spec: http://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0333

WSGI Parts¶

WSGI consists of two parts, a server and an application.

A WSGI Server must:

- set up an environment, much like the one in CGI

- provide a method

start_response(status, headers, exc_info=None) - build a response body by calling an application, passing

environmentandstart_responseas args - return a response with the status, headers and body

A WSGI Appliction must:

- Be a callable (function, method, class)

- Take an environment and a

start_responsecallable as arguments - Call the

start_responsemethod. - Return an iterable of 0 or more strings, which are treated as the body of the response.

Here is some pseudocode that outlines what basic functions a WSGI server must implement:

from some_application import simple_app

def handle_request(request, app):

environ = build_env(request)

iterable = app(environ, start_response)

for data in iterable:

send_response(data)

def build_env(request):

# put together some environment info from the reqeuest

return env

def start_response(status, headers):

# start an HTTP response, sending status and headers

# listen for HTTP requests and pass on to handle_request()

serve(simple_app)

Where the simplified server above is not functional, this is a complete app:

def application(environ, start_response)

status = "200 OK"

body = "Hello World\n"

response_headers = [('Content-type', 'text/plain'),

('Content-length', len(body))]

start_response(status, response_headers)

return [body]

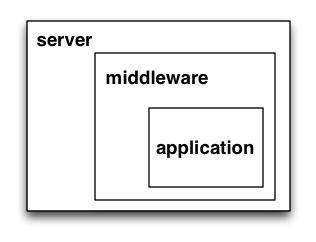

So, WSGI consists of servers and applications. But there’s actually a third part of the puzzle. Something called WSGI middleware

- Middleware implements both the server and application interfaces

- Middleware acts as a server when viewed from an application

- Middleware acts as an application when viewed from a server

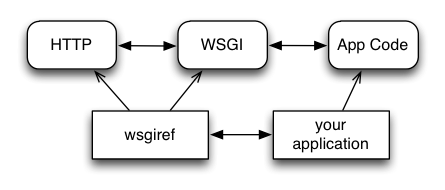

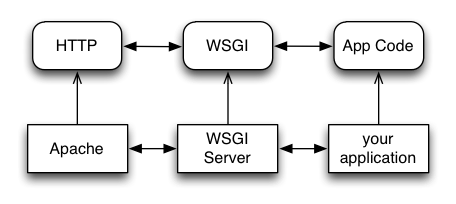

WSGI Flow¶

WSGI Servers:

HTTP <—> WSGI

WSGI Applications:

WSGI <—> app code

So the WSGI Stack can be expressed like this:

HTTP <—> WSGI <—> app code

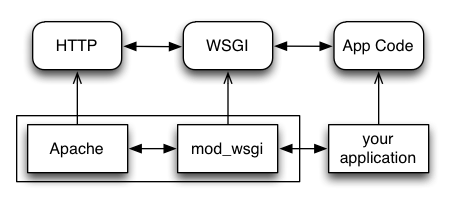

Serving WSGI Apps¶

There are a number of different ways of serving WSGI apps.

Using wsgiref

The Python standard lib provides a reference implementation of WSGI:

Apache mod_wsgi

You can also deploy with Apache as your HTTP server, using mod_wsgi:

Proxied WSGI Servers

Finally, it is also common to see WSGI apps deployed via a proxied WSGI server:

WSGI Environment¶

WSGI shares the concept of environment with CGI.

In WSGI the environment is explicitly built and passed to the application.

WSGI does not make use directly of os.environ.

But what is in the WSGI environment should look familiar:

REQUEST_METHOD

The HTTP request method, such as "GET" or "POST". This cannot ever be an

empty string, and so is always required.

SCRIPT_NAME

The initial portion of the request URL's "path" that corresponds to the

application object, so that the application knows its virtual "location".

This may be an empty string, if the application corresponds to the "root" of

the server.

PATH_INFO

The remainder of the request URL's "path", designating the virtual

"location" of the request's target within the application. This may be an

empty string, if the request URL targets the application root and does not

have a trailing slash.

QUERY_STRING

The portion of the request URL that follows the "?", if any. May be empty or

absent.

CONTENT_TYPE

The contents of any Content-Type fields in the HTTP request. May be empty or

absent.

CONTENT_LENGTH

The contents of any Content-Length fields in the HTTP request. May be empty

or absent.

SERVER_NAME, SERVER_PORT

When combined with SCRIPT_NAME and PATH_INFO, these variables can be used to

complete the URL. Note, however, that HTTP_HOST, if present, should be used

in preference to SERVER_NAME for reconstructing the request URL. See the URL

Reconstruction section below for more detail. SERVER_NAME and SERVER_PORT

can never be empty strings, and so are always required.

SERVER_PROTOCOL

The version of the protocol the client used to send the request. Typically

this will be something like "HTTP/1.0" or "HTTP/1.1" and may be used by the

application to determine how to treat any HTTP request headers. (This

variable should probably be called REQUEST_PROTOCOL, since it denotes the

protocol used in the request, and is not necessarily the protocol that will

be used in the server's response. However, for compatibility with CGI we

have to keep the existing name.)

HTTP_ Variables

Variables corresponding to the client-supplied HTTP request headers (i.e.,

variables whose names begin with "HTTP_"). The presence or absence of these

variables should correspond with the presence or absence of the appropriate

HTTP header in the request.

A Simple WSGI App¶

Let’s create ourselves a simple WSGI app so that we can see this in action.

In your terminal, kill the CGIHTTPServer and then move up and out of the

cgitests directory.

Make a new directory called wsgitests and create a new file in it called

simple_app.py. Then open that in your editor:

heffalump:cgitests cewing$ cd ..

heffalump:tests cewing$ mkdir wsgitests

heffalump:tests cewing$ touch wsgitests/simple_app.py

heffalump:tests cewing$ subl wsgitests/

In your new file, enter the following code:

def application(environ, start_response):

line_tmpl = "Key: {} Value: {}\n"

body_length = 0

response = []

for key, val in environ.items():

line = line_tmpl.format(key, val)

response.append(line)

body_length += len(line)

status = '200 OK'

response_headers = [('Content-Type', 'text/plain'),

('Content-Length', str(body_length))]

start_response(status, response_headers)

return response

Then, at the bottom of the file, add the following __main__ block:

if __name__ == '__main__':

from wsgiref.simple_server import make_server

srv = make_server('localhost', 8080, application)

srv.serve_forever()

Note

We do not define start_response, the application does that.

We are responsible for determining the HTTP status.

You can now start up a wsgi server by running this script at the command line:

heffalump:wsgitests cewing$ python simple_app.py

What host and port will it use?

Point your browser at http://localhost:8080/. Did your application work?

Look over the names and values present in the WSGI environment. What parts do you think might be useful in building a more complex application?

Also notice that although we have a Python file named simple_app.py, the

name of our script does not appear in the URL. This is different from CGI.

What does this mean about our application? What does it mean if our application is to serve multiple “resources” from different URIs?

Some Tips¶

Because WSGI is a long-running process, the file you are editing is not reloaded after you edit it.

You’ll need to quit and re-run the script between edits.

However, unlike CGI, WSGI does not hijack stdout which means that you can

insert breakpoints into WSGI application code and interact with the code in a

debugger.

Yay!