Deep Dive into Class-Based Views¶

The DetailView¶

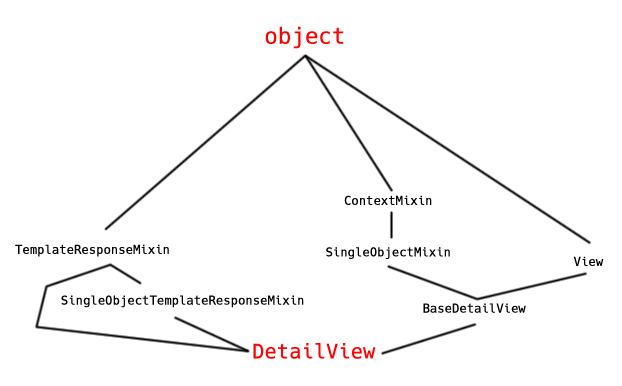

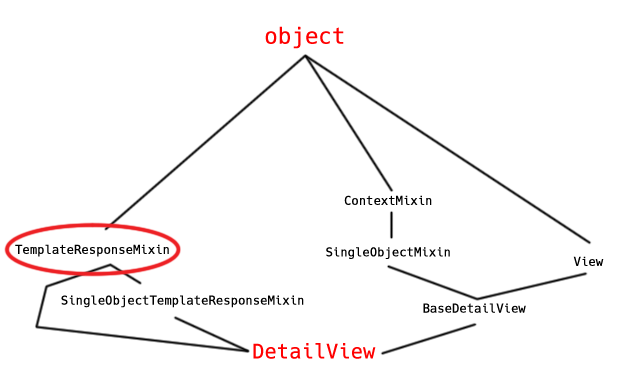

Let’s take a deep dive into the inheritance structure of the DetailView and a walk through a single GET request.

Class-based views (CBVs) use class inheritance. They also use the “mixin” pattern.

- You create classes with specific, related functionality

- You can include that class as a parent of another classes

In your terminal, navigate to the directory containing the django_lender, then to ENV/lib/python3.6/site-packages/

You can see in there some of the installed packages required to make Django work.

Now use your editor to open the django directory in the site-packages directory.

We’re going to pick one of our generic views and inspect it.

We’ll start with the DetailView

It’s worth our time to learn how this class is put together and to understand the Method Flowchart so that we can spelunk down through these methods and see what we may want to use, as well as what we may want to override.

Open up in your editor django/views/generic/.

When we open a view such as the DetailView, we use from django.views.generic import DetailView.

What does that mean in terms of the structure of this package?

Where will we look for the DetailView?

The generic directory has a file in it called __init__.py.

This file creates an API for Django’s generic package.

It imports into its own namespace a whole bunch of modules that are inside the generic package, that would on their own be spread across various files.

It uses a trope called the special __all__ attribute.

This attribute says, if you would like to import from django.views.generic, here are all of the symbols available to you:

...$VIRTUAL_ENV/lib/python3.6/site-packages/django/views/generic/init.py

...

__all__ = [

'View', 'TemplateView', 'RedirectView', 'ArchiveIndexView',

'YearArchiveView', 'MonthArchiveView', 'WeekArchiveView', 'DayArchiveView',

'TodayArchiveView', 'DateDetailView', 'DetailView', 'FormView',

'CreateView', 'UpdateView', 'DeleteView', 'ListView', 'GenericViewError',

]

...

If you want to learn where something is defined, you can come here to __init__.py and look for the import statement:

from django.views.generic.detail import DetailView

Let’s open django/views/generic/detail.py now.

Find the DetailView class definition:

...$VIRTUAL_ENV/lib/python3.6/site-packages/django/views/generic/detail.py

class DetailView(SingleObjectTemplateResponseMixin, BaseDetailView):

"""

Render a "detail" view of an object.

By default this is a model instance looked up from `self.queryset`, but the

view will support display of *any* object by overriding `self.get_object()`.

"""

We see here that DetailView doesn’t define a single thing itself.

DetailView inherits from SingleObjectTemplateResponseMixin and BaseDetailView.

Scrolling up (or text search), we can inspect the SingleObjectTemplateResponseMixin.

It inherits from TemplateResponseMixin.

Now we’ll look at BaseDetailView, and it inherits from a couple of things:

SingleObjectMixinView

SingleObjectMixin inherits from ContextMixin.

ContextMixin comes from this import: from django.views.generic.base import ContextMixin, TemplateResponseMixin, View

We need to go deeper. DjangoCeption.

Open base.py from the generic directory.

...$VIRTUAL_ENV/lib/python3.6/site-packages/django/views/generic/base.py

So we find that ContextMixin, TemplateResponseMixin, and View all inherit from object here, and that’s the root of our inheritance tree.

This is multiple inheritance.

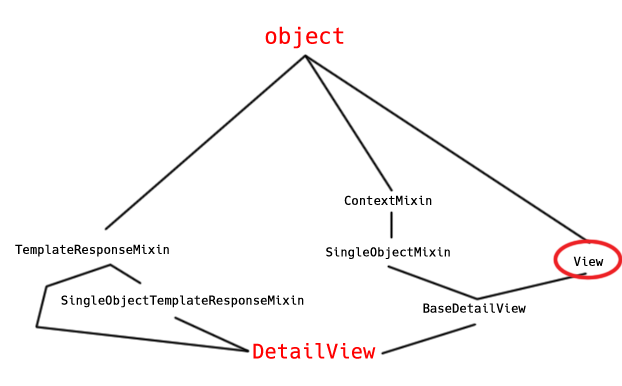

So let’s go back to our View class, and imagine that we have made a GET request to the /library/books/1 route.

We would expect this to show us a book, with an id of 1.

(GET http://oursite.com/library/books/1 HTTP/1.1)

Let’s inspect View:

...$VIRTUAL_ENV/lib/python3.6/site-packages/django/views/generic/base.py

...

class View(object):

"""

Intentionally simple parent class for all views. Only implements

dispatch-by-method and simple sanity checking.

"""

http_method_names = ['get', 'post', 'put', 'patch', 'delete', 'head', 'options', 'trace']

...

@classonlymethod

def as_view(cls, **initkwargs):

"""

Main entry point for a request-response process.

"""

for key in initkwargs:

if key in cls.http_method_names:

raise TypeError("You tried to pass in the %s method name as a "

"keyword argument to %s(). Don't do that."

% (key, cls.__name__))

if not hasattr(cls, key):

raise TypeError("%s() received an invalid keyword %r. as_view "

"only accepts arguments that are already "

"attributes of the class." % (cls.__name__, key))

...

Let’s walk through this code.

- We define a

@classonlymethod. This means it is probably only available on the class and not on an instance. Is it a Django specific construct? Yes, it seems so. - The

as_viewmethod iterates over an object calledinitkwargs. For each key in theinitkwargs, it checks whether the key is in thecls.http_method_names. If it is, Django raises aTypeErrorwith a helpful message. If not, it moves on to check whether the key is an attribute of the class. If it is not, aTypeErroris raised with a helpful message.

Think about yesterday where we passed arguments to as_view(), something like template_name="lending_library/home.html".

If the keyword passed to this class is available, it will accept it.

If not it will reject it with a message.

In other words, any attribute of this class can be overridden in the call to as_view().

Next we have a view method.

It accepts request, *args, **kwargs).

It binds self to the class attributes **initkwargs.

If self hasattr('get') and does not hasattr('head'), we will bind self.head = self.get.

- Normally what

headis suppose do to is return headers of the response without returning a response.

The important part is next:

- It binds

self.request = request - It binds

self.args = args - It binds

self.kwargs = kwargs

What kind of a function is this?

def view(request, *args, **kwargs):

It’s a function based view - much like what we built last Tuesday.

A function based view is a function that takes a request as the first argument, and may or may not have positional or keyword arguments that are passed to it as a result of the URL pattern that it matches.

This is the most generic possible call signature to represent any possible view.

It will accept any positional arguments and any keyword arguments, and it will accept request as the first positional argument.

This is what is returned when the as_view() method is called.

This means we are creating, as a result of calling as_view(), a function that has self baked into it, that will end up being called when that particular URL is matched.

What we’re doing is creating a function that wraps around an instance of our class, and then executes dispatch() on that instance.

Remember what Django does:

- It takes a URL from the initial HTTP request

- It looks at the URL and tries to match it to one of the patterns defined in the

urlpatternslist inlending_library/lending_library/urls.py. - When it does, it then extracts from the URL the

*argsand**kwargsthat are part of the URL, as specified by the?Ppattern in the route declaration. - It takes the request, the

*args, and the**kwargsand passes those off to a call of the function that it has been bound to in your url configuration. This may be a function-based view that takes these directly or theas_view()method of a class-based view.def view(request, *args, **kwargs):is that function for a class based view.

What this means is that the first method that every single class-based view that inherits from View will see is the dispatch() method.

Let’s look at dispatch() now, and see what it does.

CBV dispatch()¶

...$VIRTUAL_ENV/lib/python3.6/site-packages/django/views/generic/base.py

class View(object):

...

def dispatch(self, request, *args, **kwargs):

# Try to dispatch to the right method; if a method doesn't exist,

# defer to the error handler. Also defer to the error handler if the

# request method isn't on the approved list.

if request.method.lower() in self.http_method_names:

handler = getattr(self, request.method.lower(), self.http_method_not_allowed)

else:

handler = self.http_method_not_allowed

return handler(request, *args, **kwargs)

We know the first stop on our trip will be the View class, and it is there that we will call dispatch().

- Conditional check to see if the

request.methodis in thehttp_method_names.- If it’s not, it sets

handler = self.http_method_not_allowedand then calls that method. Then it does some logging. - If it is, we set handler to either the method that matches the request, or

http_method_not_allowedif that particular method is not allowed.

- If it’s not, it sets

In our case here, what is our HTTP method? GET.

What’s the next call that will happen here then?

We’ll call the self.get() method of our DetailView class.

Is there a get() method on our View class?

It doesn’t look like it.

It could come from any of our classes that DetailView inherits from!

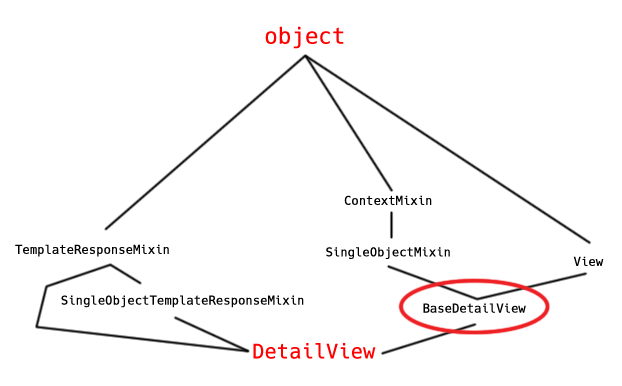

If we look hard enough, we’ll find it in BaseDetailView.

So, stop number 2 in our trip is the get() method of class BaseDetailView:

django/views/generic/detail.py

class BaseDetailView(SingleObjectMixin, View):

"""

A base view for displaying a single object

"""

def get(self, request, *args, **kwargs):

self.object = self.get_object()

context = self.get_context_data(object=self.object)

return self.render_to_response(context)

Let’s walk through this.

get()accepts therequest,*args,**kwargs.- It binds

self.objecttoself.get_object() - It binds

contexttoself.get_context_data(object=self.object) - It returns

self.render_to_response(context)

Mostly we just call a bunch of other methods and then return the context.

Let’s search for get_object() now and see what it does.

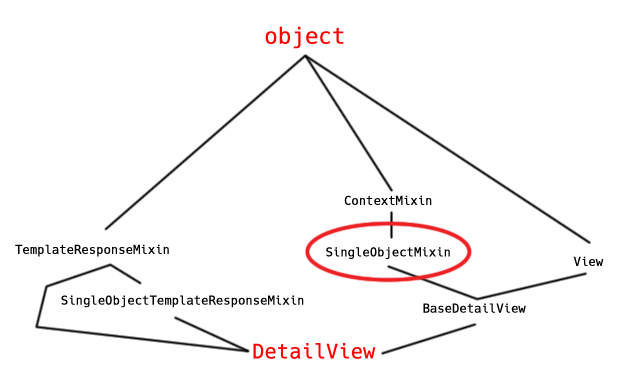

It’s found in the SingleObjectMixin class, so that’s the next stop on our journey.

django/views/generic/detail.py

class SingleObjectMixin(ContextMixin):

"""

Provides the ability to retrieve a single object for further manipulation.

"""

model = None

queryset = None

slug_field = 'slug'

context_object_name = None

slug_url_kwarg = 'slug'

pk_url_kwarg = 'pk'

query_pk_and_slug = False

def get_object(self, queryset=None):

"""

Returns the object the view is displaying.

By default this requires `self.queryset` and a `pk` or `slug` argument

in the URLconf, but subclasses can override this to return any object.

"""

# Use a custom queryset if provided; this is required for subclasses

# like DateDetailView

if queryset is None:

queryset = self.get_queryset()

# Next, try looking up by primary key.

pk = self.kwargs.get(self.pk_url_kwarg, None)

slug = self.kwargs.get(self.slug_url_kwarg, None)

if pk is not None:

queryset = queryset.filter(pk=pk)

# Next, try looking up by slug.

if slug is not None and (pk is None or self.query_pk_and_slug):

slug_field = self.get_slug_field()

queryset = queryset.filter(**{slug_field: slug})

# If none of those are defined, it's an error.

if pk is None and slug is None:

raise AttributeError("Generic detail view %s must be called with "

"either an object pk or a slug."

% self.__class__.__name__)

try:

# Get the single item from the filtered queryset

obj = queryset.get()

except queryset.model.DoesNotExist:

raise Http404(_("No %(verbose_name)s found matching the query") %

{'verbose_name': queryset.model._meta.verbose_name})

return obj

What does it do? What are the attributes that are available here on this class?

- There’s a

modelattribute. We can probably guess what it does. - There’s a

querysetattribute. We can probably guess what it does. If we passed inmodel.objectsthat would be aqueryset. - There’s a

slugfield - There’s a

context_object_namefield - a

slug_url_kwarg - a

pk_url_kwarg - a

query_pk_and_slug

What do these attributes mean? What can we do with them?

Remember our as_view() method?

Anything that is an attribute of the View class can be passed in as a keyword argument to the as_view() call.

All of these attributes are customization points to our DetailView.

The get_object method¶

What does get_object() do? (Student reads through code):

- If we don’t have a

queryset, then we setquerysetto the value ofself.get_queryset()- Let’s hold of for a minute exploring this

- We set our

pk(primary key) to what is inself.kwargs- We got this from our

dispatch()method where we set up ourviewfunction, and on that we built an instance ofselfand we setself.request, self.args, self.kwargsto be the arguments and keyword arguments that were passed into that view function. So this is whatever kwargs came in from our URL. - So we set

pkto thepk_url_kwargvalue, orNone

- We got this from our

- We do the same for

slug

So our slug_url_kwarg and pk_url_kwarg are being used as a key for a dictionary lookup in the kwargs that got passed to us as part of our View call.

If we use a primary key in our URL, then magically when our view() method gets called, that pk keyword argument will be present in self.kwargs.

This means when we try to get pk from self.kwargs, we will get the value present there which in our case will be 1.

So our pk will not be None.

What do we do with it if it’s not None?

We take the queryset that we have built by calling self.get_queryset, and we filter that queryset to show us only those objects that have our pk.

If this works, then great!

Otherwise we can try and do the same thing with the slug, where we’re filtering on the slug.

Otherwise we raise an AttributeError that states that we need either a pk or slug.

What happens here?:

try:

# Get the single item from the filtered queryset

obj = queryset.get()

except queryset.model.DoesNotExist:

raise Http404(_("No %(verbose_name)s found matching the query") %

{'verbose_name': queryset.model._meta.verbose_name})

return obj

- We try the

.get()method on ourqueryset - If that results in an exception of

queryset.model.DoesNotExistthen we raise a 404 error. - Otherwise we return whatever

objis.

So let’s look at this in the context of a site that wants to show photos.

Maybe you want to sort out into photos that are published and ones that are not.

This get_queryset() method could allow you to provide a view here that only returns published photos.

Let’s look now for get_queryset(). It’s right below:

def get_queryset(self):

"""

Return the `QuerySet` that will be used to look up the object.

Note that this method is called by the default implementation of

`get_object` and may not be called if `get_object` is overridden.

"""

if self.queryset is None:

if self.model:

return self.model._default_manager.all()

else:

raise ImproperlyConfigured(

"%(cls)s is missing a QuerySet. Define "

"%(cls)s.model, %(cls)s.queryset, or override "

"%(cls)s.get_queryset()." % {

'cls': self.__class__.__name__

}

)

return self.queryset.all()

- If there is not a

queryset, then go to the model and get the_default_managerand call theall()method on it. - Otherwise if you don’t have a model or

querysetthen anImproperlyConfigurederror is thrown that says “we have no idea what you are looking for”.

Remember, model and queryset are available to you as arguments.

So, you can specify the model, and then override the get_queryset() method to call super().get_queryset() that would hand you back all objects, then you can filter that queryset on only those that are published.

This is how our custom subclasses of models.ModelManager work!

Inside that set of filtered objects, we could look for the one that has the given primary key, and give that back or raise 404. Now we’re getting a sense of the path we take to get through a call.

A Little More About get_context_data()¶

Going back to our BaseDetailView, the next thing it does is call get_context_data():

django/views/generic/detail.py

...

class SingleObjectMixin(ContextMixin):

...

def get_context_object_name(self, obj):

"""

Get the name to use for the object.

"""

if self.context_object_name:

return self.context_object_name

elif isinstance(obj, models.Model):

return obj._meta.model_name

else:

return None

def get_context_data(self, **kwargs):

"""

Insert the single object into the context dict.

"""

context = {}

if self.object:

context['object'] = self.object

context_object_name = self.get_context_object_name(self.object)

if context_object_name:

context[context_object_name] = self.object

context.update(kwargs)

return super(SingleObjectMixin, self).get_context_data(**context)

...

- First we set our context to an empty dictionary.

- If

self.objectexists:- Set

context['object'] = self.object - Set

context_object_nameto the return ofget_context_object_name(self.object)- If we have a

context_object_name, return it - Else if our object is an instance of a

Model, return the name of the model. - Else return

None

- If we have a

- Set

Given no customization to any of our attributes, which happen to include context_object_name, what keys in our context dictionary will point at the object that we are looking for?

We have get_context_data().

It’s already set up one name for it.

It’s not setting up a second name to look at.

If we want to refer to our object in a template, how do we refer to it?

In this case get_context_object_name will get the name of the Model (like Photo or Book).

If we wanted to call it Potato, then when we call as_view() in our URLconf, we could pass the context_object_name keyword argument, and point it at Potato.

Then Potato would be available to us in our template.

So, we’ve gotten the context_object_name, and now we are doing what?

context.update(kwargs) to add our kwargs to the context.

Lastly we call super for the .get_context_data(**context).

django/views/generic/base.py

class ContextMixin(object):

"""

A default context mixin that passes the keyword arguments received by

get_context_data as the template context.

"""

def get_context_data(self, **kwargs):

if 'view' not in kwargs:

kwargs['view'] = self

return kwargs

So all this does is take the kwargs and says: if we don’t have the view object itself in our kwargs, then go ahead and add it and return kwargs.

This ensures that the actual view itself is included as part of the context that gets passed to our template.

What that means is that in the context of your template you can refer to your view class that is powering that template.

The Next Step in the Process¶

So there are are a couple of other classes in our inheritance path that came from various places in this hierarchy.

You can see that it can become complicated.

Let’s go back to our BaseDetailView and look at the get() method again.

What’s the last thing that happens after we’ve gotten our context data?

return self.render_to_response(context)

We call the render_to_response method and pass the context.

So let’s look at render_to_response

render_to_response¶

django/views/generic/base.py

...

class TemplateResponseMixin(object):

"""

A mixin that can be used to render a template.

"""

template_name = None

template_engine = None

response_class = TemplateResponse

content_type = None

def render_to_response(self, context, **response_kwargs):

"""

Returns a response, using the `response_class` for this

view, with a template rendered with the given context.

If any keyword arguments are provided, they will be

passed to the constructor of the response class.

"""

response_kwargs.setdefault('content_type', self.content_type)

return self.response_class(

request=self.request,

template=self.get_template_names(),

context=context,

using=self.template_engine,

**response_kwargs

)

...

So our render_to_response() method gets called with a context and optionally some keyword arguments.

Does our current call pass any keyword arguments besides context?

No. What does this method do?

response_kwargsare set to{"content_type": self.content_type}- We return the value of

self.response_class()- Passing in

request templatecontextusing(which template engine)- any

**response_kwargs

- Passing in

get_template_names() returns a list of templates to be used for the request.

Does SingleObjectTemplateResponseMixin have a get_template_names() method too? Hell yes it does.

django/views/generic/detail.py

class SingleObjectTemplateResponseMixin(TemplateResponseMixin):

template_name_field = None

template_name_suffix = '_detail'

def get_template_names(self):

"""

Return a list of template names to be used for the request. May not be

called if render_to_response is overridden. Returns the following list:

* the value of ``template_name`` on the view (if provided)

* the contents of the ``template_name_field`` field on the

object instance that the view is operating upon (if available)

* ``<app_label>/<model_name><template_name_suffix>.html``

"""

try:

names = super(SingleObjectTemplateResponseMixin, self).get_template_names()

except ImproperlyConfigured:

# If template_name isn't specified, it's not a problem --

# we just start with an empty list.

names = []

# If self.template_name_field is set, grab the value of the field

# of that name from the object; this is the most specific template

# name, if given.

if self.object and self.template_name_field:

name = getattr(self.object, self.template_name_field, None)

if name:

names.insert(0, name)

# The least-specific option is the default <app>/<model>_detail.html;

# only use this if the object in question is a model.

if isinstance(self.object, models.Model):

names.append("%s/%s%s.html" % (

self.object._meta.app_label,

self.object._meta.model_name,

self.template_name_suffix

))

elif hasattr(self, 'model') and self.model is not None and issubclass(self.model, models.Model):

names.append("%s/%s%s.html" % (

self.model._meta.app_label,

self.model._meta.model_name,

self.template_name_suffix

))

# If we still haven't managed to find any template names, we should

# re-raise the ImproperlyConfigured to alert the user.

if not names:

raise

return names

- First we try setting

namesto thesuperofget_template_names(). This looks back up to the previousget_template_names()method we were just looking at. - If that doesn’t work, we’ll raise an

ImproperlyConfigurederror. - We then set names to an empty list

- We check to see if this instance has an

objectattribute, and atemplate_name_field.- If it has both of those:

- We set

nameto be the attribute onself.objectthat matches thetemplate_name_field- it setsNoneif it can’t find it - If

nameis set, it’s inserted into the front ofnames

- We set

- If

self.objectis an instance ofmodels.Model:- We append to the

nameslist:self.object._meta.app_labelself.object._meta.model_nameself.template_name_suffix- which defaults to_detail

- We append to the

- If it has both of those:

- Return the

names

We’re providing a list of possible template names that we’re looking for.

We can override that template name by providing a template_name in the call to as_view().

We can provide another version of that template name by setting up the template_name field and then storing in maybe the database the name of the template that we want to use for this particular object.

So that takes us back to BaseDetailView where we were calling render_to_response() which was coming from our TemplateResponseMixin.

What’s the implication of content_type = None?

It could be HTML, text, json... You could override the content_type value, and maybe override the template.

This is pretty much the simplest of the CBVs in Django. The other ones get worse from here.

A Few Final Notes¶

Django is notorious..

Zope went down this road about 10 years ago.

They made all these classes and mixins and eventually when you ran dir() on a view you’d end up like 800 items in it.

Django is doing the same thing.

It’s becoming a mess.

But if you’re going to use Django you need to understand how these CBVs work. Diving in and following the code is the best way to understand these views.

For your assignments you will really only be interested in the DetailView, ListView, CreateView, and UpdateView.

You will only one to look at a single photo, or a list of them, etc.

This is all pretty confusing and annoying having to wade through all of these Class inheritance hierarchies, but if you understand them you can really harness the power of them. And you’ll need to. While these CBVs work pretty well out of the box, as soon as you want to depart from their exact specification you’ll need to crack them open and muck about in their insides. Having gone through this exercise now, you’ll at least have some experience at seeing the internal flow of Django.