Files in Django¶

In this lecture we will go over dealing with files and the filesystem when working with Django. Our site works with binary data in the form of files. These files represent book covers that our users upload to our system. We’ll go over how to set up our models and filesystem to make all of this work.

A New Application¶

Django encourages developers to build individual units of functionality for a site in individual apps. Imagine for a moment a website that caters to comic book fans. It might have a system for listing given comic book titles, different runs within each title, and then individual issues. This system would be an “app”. Perhaps the site might also have a forum section, where users can open and participate in discussions about their favorite comic books. This forum would likely be a separate app. The app is used in this site to discuss comic books. But if it is well written, there would be nothing that prevent it from being used in a different website to discuss other topics.

We already have one app in our Django Lender site. It manages user profiles for us. But there is no reason that app should also contain the models and views needed to manage books.

We need to start a new app that will represent the book management portion of our website.

Move into your django_lender site directory (with the manage.py).

Start a new app:

$ python manage.py startapp lender_books

We can begin by starting to build our model:

/.../lending_library/lender_books

from django.db import models

import datetime

class Book(models.Model):

cover_image = models.ImageField

title = models.CharField(max_length=255)

author = models.CharField(max_length=255)

YEARS = [(year, year)

for year in range(1, datetime.datetime.now().year + 1)][::-1]

year = models.IntegerField(choices=YEARS, default=2016)

BOOK_STATUS = [

("available", "Available"),

("checked out", "Checked Out")

]

status = models.CharField(

max_length=20,

choices=BOOK_STATUS,

default="available"

)

date_added = models.DateTimeField(auto_now_add=True)

last_borrowed = models.DateTimeField(auto_now=True)

Let’s start with a cover_image field: cover_image = models.ImageField.

Django has 2 types of fields when dealing with binary files, the ImageField and the FileField.

Images are just files that have special properties like height and width.

Django comes with this functionality built in with ImageField.

When we construct these models, there are a few options we really want to think about.

The first of these is upload_to.

Files and Media¶

Here is our FileField constructor:

class FileField(upload_to=None, max_length=100, **options)

- It takes

upload_to=Noneas a default. - It takes

max_length=100as a default. - It takes

**options(more on these later).

upload_to represents a filesystem path where we will store these images.

Django keeps track for you of a place called MEDIA_ROOT.

We need to add this to settings.py.

It’s not a normal default setting because not all sites require the ability to upload files.

If we look in our settings.py file, you’ll see a setting called BASE_DIR = os.path.dirname(os.path.dirname(os.path.abspath(__file__))).

This is a bit confusing, but here is what it does.

It calls os.path.abspath(__file__) on settings.py.

This gives us the absolute path to our settings.py file as a starting point.

Calling os.path.dirname() on that path hands us back everything in the path except the last path segment.

In this case, that strips the filename and leaves us with the path to the directory containing the settings.py file, our configuration root.

Calling dirname() again on that value again strips the last path segement.

That gives us the path to the directory that contains our configuration root, the project root:

$ tree .

.

├── lender_books

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── admin.py

...

├── lending_library

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── __init__.pyc

│ ├── settings.py

...

└── manage.py

So in our current directory structure, we would be setting BASE_DIR to the directory one level above our settings.py.

This is the directory in which manage.py is located.

The way that startproject works, it always gives you this structure.

You can rename the top-level site directory if you want to, but do not change the name of the directory with your settings.py file.

The reason for this is because in your manage.py file, it refers to your lending_library.settings.

You would need to start renaming things in other places as well, or your site will stop working properly.

MEDIA_ROOT¶

So if we want to construct a path name, what will we use?

The os module from the Python standard library provides us with os.path.join().

What does .join() take? Path segments that get joined together.

So we can set up our MEDIA_ROOT like so:

/.../lending_library/lending_library/settings.py

...

# Media file handling

MEDIA_ROOT = os.path.join(BASE_DIR, 'media')

Now our MEDIA_ROOT is set to be a folder called media that’s in our project directory.

We will need to create that folder.

You wouldn’t want to add a bunch of testing images or things your users upload as versioned items in your github repo.

But simply adding the media directory to .gitignore in this way will make it so that git doesn’t track the media directory at all.

And since Django itself will not create that directory on our behalf, this opens up a quandry.

We want this folder as a part of our project structure, but we don’t want anything inside it.

The best way to accomplish this is to go into the media directory and add a file called .gitkeep.

This file could really be called anything, .gitkeep is just a convention.

The point is that there is now a file inside that directory, which means git can track it.

Now we’ll see the media directory in our git status of untracked files.

If we commit this file, then the media directory will now be added to our directory structure.

To prevent anything else that is created there from being committed, we can add media/* to our .gitignore.

Alternatively, we can add two lines, media and !media/.gitkeep, which ignores the directory, but exempts the .gitkeep file from that rule.

.gitignore

...

media

!media/.gitkeep

Gotchas¶

Getting back to MEDIA_ROOT.

Whenever you upload a file to Django, that’s where Django will put the actual files that were uploaded.

When you set something up like the Book class like we’re making, this upload_to argument will be appended to the MEDIA_ROOT directory.

The resulting path will be the location where the data from the uploaded file will be written to disk.

Be careful not to add “/” before the name you provide as the value for upload_to.

Django will throw an error here that might not make a lot of sense at first glance.

It will complain about a security violation.

The reason is that like us, Django uses os.path.join() to build the complete path.

What happens when you join two paths that start with / using that function?

In [1]: import os

In [2]: path1 = "/absolute/path/one"

In [3]: path2 = "/another/path"

In [4]: os.path.join(path1, path2)

Out[4]: '/another/path'

The end result is that you end up with only the second path, treated as an absolute path.

Django tries to spot this.

If the final result for the path where you want to store files is not located inside the value of MEDIA_ROOT it will throw an error.

It will assume that someone is trying to pass bad user data to break out of system containment on your server.

So the end result of our file field declaration for a Book model should look something like this.

/.../django_lender/lending_library/lender_books

from django.db import models

class Book(models.Model):

cover_image = models.ImageField(upload_to='book_covers')

Now we’re set up to upload files, and Django will take care of the file management of them for us.

Options for upload_to¶

You can also pass strings into the upload_to field that are for formatting in date-time style.

cover_image = models.ImageField(upload_to='book_covers/%Y-%m-%d')

If you are planning on working with a large number of files, this is actually a great idea. File systems have a limited number of nodes they can open, so this is one way to limit the number of files in one directory.

The final option for upload_to is to pass a Python callable.

The callable will be executed when the file is uploaded.

It will receive the instance of the model where the file field is defined as the first argument.

The second argument will be the filename of the uploaded file.

This callable should be used to assemble a relative pathname for the file to be written to.

This example shows how to write each Book into a directory named for its own user.

def user_directory_path(instance, filename):

# file will be uploaded to MEDIA_ROOT/user_<id>/<filename>

return 'user_{0}/{1}'.format(instance.user.id, filename)

Media URLs¶

Now we’ve created this ImageField, and our users’ Books will be uploaded to known locations.

In order for them to be viewed, we need to be able to construct a url that points to the file.

Django provides automatically a STATIC_URL setting in the settings.py file.

In the default skeleton we’ve been given, what is that value?

This becomes an initial path value used to construct URLs for static resources like javascript and css.

By default, during development, Django will look in static directories in any installed apps for these resources.

We can also create a STATIC_ROOT = os.path.join(BASE_DIR, 'static') that points to a single home for static resources.

Then the collectstatic management command will copy all the static resources of all our installed apps into that location.

Media resources (files uploaded by users, but not part of the site itself) work in a similar fashion.

We can set a MEDIA_URL value in settings.py to allow Django to build the right URLs for us.

But there’s a bit of a problem that will stand in our way.

Django uses a urlconf to map URIs to a particular view.

For example, we can include all the URLs for views that correspond to our patron_profile app:

/.../lending_library/lending_library/urls.py

urlpatterns = [

url(r'^admin/', include(admin.site.urls)),

url(r'^profile/', include('patron_profile.urls')),

]

This will buckle all of the urls in our patron_profile so that they start with profile/ in the URL.

Other apps may be buckled in at other path segments.

This should not be overly surprising to us.

The problem we are trying to solve is that we want to get to our MEDIA resources.

In Django the FileField itself is responsible for generating the URL at which that file can be viewed.

In point of fact, it isn’t the field itself, but rather a thing called a “storage” which is responsible for determining where that file data is written.

But for the time being we can think of it as the field.

This is best illustrated by example.

Let’s start by registering our new, simple Book model for Django’s admin.

/.../lending_library/lender_books/admin.py

from django.contrib import admin

from .models import Book

admin.site.register(Book)

Now our admin system is aware of our Book model.

Add our lender_books app to our settings.py so that Django itself knows about the models:

/.../lending_library/lending_library/settings.py

...

INSTALLED_APPS = (

'django.contrib.admin',

'django.contrib.auth',

'django.contrib.contenttypes',

'django.contrib.sessions',

'django.contrib.messages',

'django.contrib.staticfiles',

'django.contrib.gis',

'patron_profile',

'lender_books',

)

...

And now make migrations to register the changes to our database:

$ python manage.py makemigrations lender_books

Exploring the File API¶

At this point we get an error that Pillow is not installed.

Pillow is a python package that Django uses to work with images.

When you get this error you will need to install Pillow with pip.

$ python manage.py migrate

Now we need to create a superuser if one has not yet been created:

$ python manage.py createsuperuser

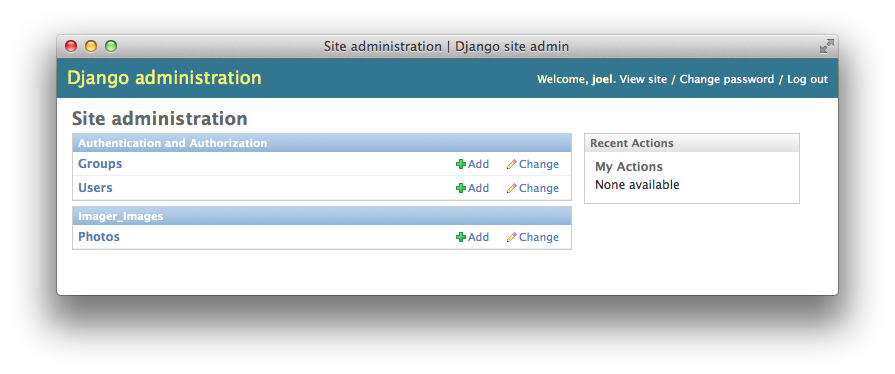

Now we have a superuser. We have a model. Our model has been hooked up to the admin so that you can interact with it in Django’s admin interface.

We can look at this by starting the Django testing server:

$ python manage.py runserver

And point our browser to http://localhost:8000/admin/

Now we should see our Book model available to us under the admin interface:

Now we can click on our Books admin and work with individual books.

There’s nothing there now, but we can add one through this interface (click the add book button and add a book).

Once we have a Book added, we can interact with it on the filesystem. Quit the development server and start up the Django shell:

$ python manage.py shell

In [1]: from lender_books.models import Book

In [2]: Book

Out[2]: lender_books.models.Book

In [3]: books = Book.objects.all()

In [4]: books

Out[4]: [<Book: Book object>]

In [5]: b1 = books[0]

In [6]: b1

Out[6]: <Book: Book object>

In [7]: b1.cover_image

Out[7]: <ImageFieldFile: book_covers/catcher_rye.jpg>

In [8]: dir(b1.cover_image)

Out[8]:

['DEFAULT_CHUNK_SIZE',

'__bool__',

'__class__',

'__delattr__',

...

'write',

'writelines',

'xreadlines']

In [9]: b1.cover_image.name

Out[9]: u'book_covers/catcher_rye.jpg'

In [10]: b1.cover_image.url

Out[10]: '/media/book_covers/catcher_rye.jpg'

What this means is that when we’re working in our views, we can grab a book object.

We can pass that book object off the the template.

And in our template we can create an image tag with something like src={{ book.cover_image.url }}.

The book file will automatically generate the URL to our book for us.

The Static View¶

Let’s consider our root URL config.

This is the place you add global URLs.

The app URLs can be imported here.

There’s one sneaky thing Django does that you might not be aware of.

Django looks at the DEBUG setting.

When it’s set to true, Django creates a url that points to static files.

It will look into each installed app and serve static files from the app if it finds them.

As soon as you set DEBUG = False, all of our CSS and other static files have broken links:

Our secret URL for static files is gone. Django’s intention is that you will use your web server to serve the static files.

Media works the same way.

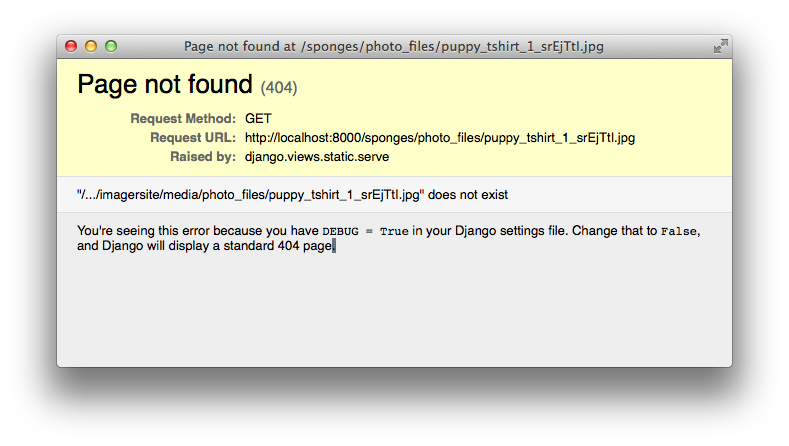

Let’s first change our DEBUG=True back. Can we navigate to our media file?

We need to look under Django’s docs to see how to deal with serving files uploaded by a user during development.

Those docs suggest to add this to urls.py:

/.../lending_library/lending_library/urls.py

from django.conf import settings

from django.conf.urls import include, url

from django.conf.urls.static import static

...

if settings.DEBUG:

urlpatterns += static(

settings.MEDIA_URL, document_root=settings.MEDIA_ROOT

)

This urlconf is identical to the one that Django itself adds for static files. We just have to do this one manually because Django does not assume we will want or need media files.

Now, your media files should be found.

Storages¶

One thing that is invisible to us that we pointed out earlier.

Our cover_image = models.ImageField() contains a file object.

That file object has an attribute called storage.

The default storage is an instance of the filesystem storage class from django.core.files.storage.

But one of the available arguments to file fields is the storage class you wish to use.

You can use other storages that allow you to automatically place your files into CDNs, an AWS S3 bucket, or any number of other scenarios.

There is a package called django storages that implements quite a number of these useful storages.

This allows you to place your files on CDNs if you want, and this can vastly speed up your static files loading around the world.

Testing Tricks¶

One last word, testing file uploads is tricky.

Take a look at the Factory Boy image field to make this easier.

Be aware that values like upload_to and MEDIA_ROOT values don’t automatically change while you are testing.

But remember that the settings you have are writable.

You can alter them at test time.

You may want to mess around with settings so that your test files go to /tmp or something like that.

See the documentation on overriding settings for ideas on how to do this.